78 RPM Sephardic Recordings

1906-1913: The First Recordings

Commercial Sephardic recording began in 1906 or 1907 in

Constantinople, when Salomon Effendi

(Salomon Algazi) recorded

Noche Buena ♪

for the Odeon Record company. (1) In a burst of activity from 1906 to

1913, four companies recorded nearly 215 Sephardic songs, laying down

most of the early masters known to us.

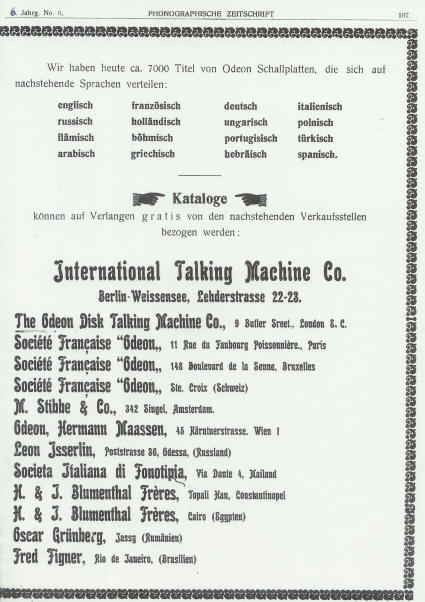

Odeon

The International Talking Machine Company

(Odeon)

was the first company to institute a system of independent agents who

worked with local artists to record local music. (2) By 1905

Odeon had amassed a catalog of hundreds of Arabic, Greek and Turkish songs.

(3) In comparison, over the next

six years Odeon released roughly two dozen double-sided Sephardic

recordings, overwhelmingly in Judeo-Spanish rather than Hebrew. Their

recording artists included

Jacob Algava,

Albert Beressi,

and the club singer Haim Effendi. This

limited slate of releases indicates the relatively small commercial

opportunity presented by Sephardic music. The International Talking Machine Company

(Odeon)

was the first company to institute a system of independent agents who

worked with local artists to record local music. (2) By 1905

Odeon had amassed a catalog of hundreds of Arabic, Greek and Turkish songs.

(3) In comparison, over the next

six years Odeon released roughly two dozen double-sided Sephardic

recordings, overwhelmingly in Judeo-Spanish rather than Hebrew. Their

recording artists included

Jacob Algava,

Albert Beressi,

and the club singer Haim Effendi. This

limited slate of releases indicates the relatively small commercial

opportunity presented by Sephardic music.

Gramophone

Odeon's arch-rival, the Gramophone Company had been the first to record in the

Ottoman Empire, in 1900. In May of that year, the Gramophone engineer

William Sinkler Darby visited Belgrade and Bucharest, then recorded

Greek and Turkish songs in Constantinople on single-sided, 7-inch

records. (4)

Around 1907, Gramophone

opened a regional office in Alexandria.

This

office handled the company's affairs for the Near East, and issued

the Greek and Turkish catalogues, including many of the so-called

"Oriental Jewish" recordings discussed here. (5) Gramophone too built up quite a catalog of Turkish, Greek and other

material before turning its attention to Sephardic recordings.

In 1907 Gramophone engineers went to Sarajevo and Constantinople, recording

masters that quickly found their way onto almost 30 releases. It's

surely no coincidence that Gramophone

added their first Sephardic titles shortly after Odeon did. The same

artists often recorded for several companies; for instance, Jacob Algava

recorded for both Odeon and Gramophone. It was also impossible to disguise

the very bulky equipment and supplies that recording engineers

carried in those days. So Gramophone representatives would

certainly have known of Odeon's Sephardic activities in advance of the

release date.

After a

two-year break, visits by Gramophone engineers to Salonica in March 1909

and Smyrna the following month yielded a new crop of recordings,

including the first by the famed cantor

Isaac Algazi.

Off the beaten track, the

expatriate Italian singer and Hazan

Alberto

della Pergola recorded four

Hebrew sides for Gramophone in Bucharest, Romania ca. August, 1913.

Some

of these Gramophone Company titles appeared on the Gramophone label,

while others were released by the

Zonophone "budget" label.

With recordings originating in Bucharest, Constantinople,

Salonica, Sarajevo and Smyrna (Izmir) (6), the Gramophone

Company had by

far the largest roster of Sephardic artists and recording locales.

Orfeon Orfeon

The first Turkish record company was founded in

late 1910 or early by the brothers Julius (pictured here)

and Hermann Blumenthal. Born in the Levant to Russian parents, the Blumenthals had previously served as local

agents for Odeon (7) (See also the advertisement, above, both courtesy of

Hugo Strötbaum.)

Shortly afterward, the brothers opened Turkey’s first record factory,

in Feriköy. They wasted no time addressing the Sephardic market in the

Ottoman Empire, releasing 45 songs by the prolific

Haim

Effendi from 1911 to 1913 on their

Orfeon and Orfeos labels. In

addition to Sephardic releases, the mainstay of the company was Turkish

music. The firm contracted "with many of the outstanding artists of the

period, foremost among whom was Tanburî Cemil Bey, as well as Hafız Âşir, Hafız Osman,

Arap Mehmet, Hanende İbrahim and Tamburacı Osman Pehlivan." In

1925, the firm sold its factory to Columbia, and re-releases

were subsequently issued on that label. (8)

Haim's recordings had an incalculable impact on Sephardim, extending

to versions of the songs collected by far-flung folkorists such as

Alberto Hemsi, Moshe Attias, Léon Algazi and Isaac Levy. "Many of these

items became standard pieces of the contemporary repertoire..." (9)

Favorite Favorite

Favorite, a German record company rounded out the field of early

entrants, with 14 songs recorded in 1912 and 1913 in Izmir, including

ten by Isaac Algazi. Though small, Favorite was an important competitor

in the Levant. Paul Blumberg, a Gramophone Company representative based in Izmir, wrote the Alexandria office in 1911, "The Favorite when

quite a small company was able to make records in February, and now

for the second time, whereas we, the great Gramophone Company, after

some two years, are meeting with all kinds of difficulties and

unpleasantness on account of a few records." (Emphasis in the original.)

(10)

The company also recorded

operettas, as well as Greek and Armenian records, and is especially

noteworthy for its recordings of artists from Izmir and Salonica. (8)

The initial repertory from these four companies was

overwhelmingly in Judeo-Spanish. Over time, Judeo-Spanish continued to

predominate, but substantially more Hebrew selections entered the

market.

Sales figures

The scarcity of surviving recordings suggests the question of how widely they were marketed. Aside from copies in record

company archives, I know of only a handful of records remaining from the entire

output of the Gramophone and Favorite companies from this early period.

Each disk likely sold at most a few thousand copies or less. (11) I

consider it most likely that only Sephardim purchased these recordings.

(12)

1914-1923:

Haim Effendi on Orfeon

For the next ten years the only recordings were made by Haim Effendi

for the Orfeon label. (See [13] for the only exception.) While

his first batch of recordings favored Judeo-Spanish over Hebrew two to

one, this next round of recordings almost exactly reversed that ratio.

Of course, World War I cast a pall over the

industry worldwide. But following the war, the 1920s were boom times for

music sales and recording activity, including other vernacular music.

But not for Sephardic music.We are left to speculate whether sales were

too modest, or if public tastes remained constant enough that no new

recordings were commercially required. Also, the wave of consolidation

that swept the European record industry meant that the surviving firms

had their pick of the recordings in the vault. In any event, there was

very little Sephardic recording activity at a time when fresh Greek,

Turkish and Balkan recordings were certainly commissioned. (14)

Haim would make only a handful of additional Sephardic recordings in his

career. As our story continues, it moves from the Ottoman lands to New

York City.

1924-1929:

New Labels and

Re-Releases

New York

The

Palomba Record and Talking Machine Co. issued one recording around

1923, with arrangements by Morris Cazes & Louis Matalon and vocal solo

by Isaac Angel. Within a year, Angel had his own boutique label, the

Angel Record Company and issued at least one more recording,

a version

of

La vida do por el raki.♪

A few more New York releases came to market. For example, both

Menachem Tsarfati and Morris Cazes (see above and the Stamboul

Quartette, below) recorded at about the same time time. I have not

been able to unearth any details.

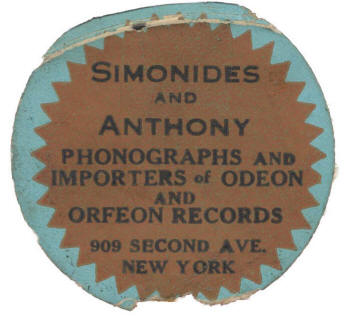

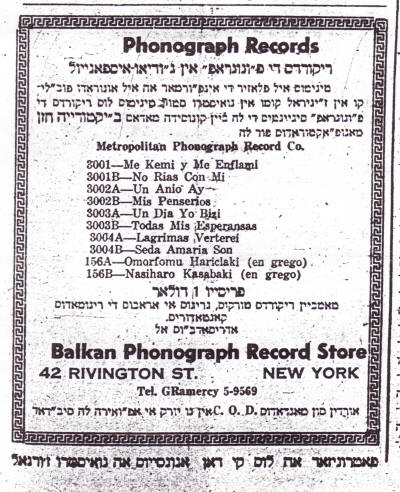

Sephardic recordings were offered for sale

at many New York City venues: the Balkan Phonograph Store, the International Phonograph Co.,

Simonides and Anthony and others. See

here for details and the advertisements. Sephardic recordings were offered for sale

at many New York City venues: the Balkan Phonograph Store, the International Phonograph Co.,

Simonides and Anthony and others. See

here for details and the advertisements.

In 1925

Columbia Records

issued the first and only Sephardic 78-rpm

recordings by a major US label: two

12" releases by the

Stamboul Quartette, whose personnel included the

previously mentioned Isaac Angel and Morris Cazes. All four songs were in Hebrew. These US

recordings do not differ appreciably from their European

counterparts in performance style. Though no one can match Isaac

Algazi's interpretive prowess, contrast

this version ♪ of Avinu Malkeinu

by the

Stamboul Quartette with

this one ♪ by Algazi.

European labels

In

late 1926 or 1927, Polydor recorded

Elias Béhar on a two-sided

Judeo-Spanish 78, accompanied by violin, 'oud

and piano (Sample.

♪) This is the first known use of a piano in a Sephardic

recording.) About the same time, the

Edison Bell

Penkala company was recording Carselero i Piadoso by Stella in Zagreb.

A tantalizing 1928

advertisement for Homocord touts the company's Hebrew, Yiddish and

Judeo-Spanish recordings (Courtesy of Dr. Rainer E. Lotz.) A tantalizing 1928

advertisement for Homocord touts the company's Hebrew, Yiddish and

Judeo-Spanish recordings (Courtesy of Dr. Rainer E. Lotz.)

Della Pergola, Albert

Pincas and possibly other artists recorded Hebrew Sephardic songs for Homocord.

Aside from the Pincas titles,

I am still seeking out further details.

In

1929 Isaac Algazi made five disks of Judeo-Spanish songs for the French

company Pathé, in addition to other Turkish works. He also completed seven

discs for Odeon.

From here forward, virtually all Sephardic

songs marketed in Europe resulted from re-releases.

Re-releases

The German branch of the Gramophone Company, Deutsche Grammophon, was

confiscated as enemy British property on April 24, 1917 and sold to

Polyphon. At war's end, unable to use the Gramophone or HMV trademarks, Polyphon issued Gramophone recordings on the Polyphon and

Polydor labels (15) Among these were eight Gramophone

Company recordings released on Polyphon sometime between the end of

World War I and fall, 1922.

Through 1931

the European recording industry underwent a dizzying series of

bankruptcies, consolidations and overseas ventures. I will try to

distill a very complex situation by discussing only those business

changes that facilitated the re-release of Sephardic recordings.

In 1913,

Favorite was folded into the Carl Lindström

A.G. family of labels. In 1920 the General Phonograph Corporation

acquired the Carl Lindström

catalogs, including Odeon and Favorite. From 1921

onward, General Phonograph Corporation drew on European masters to

produce recordings on its newly formed American Odeon label. (16) American Odeon produced a series of 16 Sephardic Odeon

re-releases, from recording sessions originally dating from 1907 and

1908, all issued by the summer of

1926. (See the catalog here.)

In 1926, Odeon and other Lindström

labels were sold to the Columbia Graphophone Co. in England and

became part of the Columbia business

in Europe. (17) After 1930, European Odeon matrices appeared for several years on

Columbia. For example, at least one

Favorite Sephardic recording was re-issued on the

Columbia label.

In a huge 1931 merger, the

Columbia Graphophone Company (which by then owned Odeon,

Favorite and many other labels) joined with the Gramophone company to

form Electric and Music Industries Ltd. (EMI). Orfeon masters

were reissued on Columbia sometime by the late 1930s.

1930s:

Art-Song Renditions

By the 1930s the global economic contraction and

the impact of radio and talking pictures hurt phonograph and record

sales dramatically (18) There were only a handful of new European recordings

dating from the 1930s, In Europe,

Léon Algazi arranged

Sephardic songs in Hebrew (sung by

Léon Gerberg ♪) and

in Ladino

(sung by

Janine Tenoudji ♪)

Albert Pincas recorded for the Ultraphon label, though

we have no release details.

(19) And the Jewish settlement in Palestine, in the person of Bracha Zefira, contributed

its first Sephardic recordings.

Bracha Zefira Bracha Zefira

Born of Yemenite parents and orphaned early in life, at the age of six Zefira

was taken in by a Sephardi widow. She heard her first Judeo-Spanish

romances from the women of the Yemin Moshe neighborhood. She later learned traditional

Sephardic songs from both Alberto Hemsi and Yitzhak Navon. Zefira

concertized extensively in the early 1930s and several Israeli composers

later arranged her song choices. (20)

Zefira's extensive public performances introduced the wider

Israeli public to Sephardic songs for the first time, and it was

squarely in an art-song, "a la Franka" (Western) style (21) Her recordings were

mastered from 1937 onward. A handful of her Hebrew Sephardic works were issued on

78, such as

Ein Adir

♪.

Various Ladino songs she performed were also set to Hebrew words, such

as Yendome (transformed into

Yesh Li Gan ♪) and

Mama yo no tengo vista, which became

Hitrag'ut. These songs and others helped form the core

of the modern Israeli Sephardi canon. (22)

It's worth noting that both these trailblazers, Bracha Zefira and

Léon Algazi,

were intimately familiar with the tradition they were adapting.

1941-1954: The End of the 78 Era

As Europe erupted in war, virtually all Sephardic

recordings of the 1940s were made in North America. And since major US

labels withdrew from the ethnic music field, it was smaller independent

labels that moved in to fill the breach. (23)

In New York, dozens of Greek-owned nightclubs on 8th Avenue from 23rd

to 42nd

street served as a haven for Greek and Armenian immigrants – as well as

Sephardim originally from the region. On stage, Albanian, Armenian,

Greek, Sephardic and other vocalists and session musicians all

contributed to the flavorful melange. Several record companies sprang up

devoted to these musicians and their audiences.

According to one account, Me-Re was

established in the early 1940s by Aydin Asllan (a poly-lingual Albanian)

and the violinist, Nick Doneff. They soon parted company, with Aydin

founding Balkan and Doneff founding Kaliphon Records. (24) Whatever the

(cross-) ownership among the Balkan, Me-Re,

Metropolitan and

Kaliphon labels, artists moved fluidly from label to label: 'Oud player

Marko Melkon recorded for all four labels, while

Victoria Hazan (see below) recorded for Metropolitan and Kaliphon.

Jack Mayesh

and Victoria Hazan

Jack Mayesh and

Victoria Hazan were the last in a

line of Sephardic artists who grew up with, performed and recorded in

the idiom of urban Ottoman music. As was characteristic of many of their

predecessors, they operated comfortably in multiple languages, and

actively set songs from other traditions to Judeo-Spanish

lyrics.

Fluent in several languages,

Victoria Hazan recorded in

Turkish, Greek and Judeo-Spanish.

Metropolitan released five of

her Judeo-Spanish recordings in early 1942, accompanied by violin, 'oud

and kanun. (See illustration at right.) Here is

El Cante por la Victoria ♪,

surely the only Ladino song to reference both Uncle Sam and Hitler!

(Lyrics here.) Fluent in several languages,

Victoria Hazan recorded in

Turkish, Greek and Judeo-Spanish.

Metropolitan released five of

her Judeo-Spanish recordings in early 1942, accompanied by violin, 'oud

and kanun. (See illustration at right.) Here is

El Cante por la Victoria ♪,

surely the only Ladino song to reference both Uncle Sam and Hitler!

(Lyrics here.)

Jack Mayesh made nine recordings for his own

Mayesh Phonograph

Records label from late 1941 to late 1943, accompanied by Gabriel Yohai on kanun. (These

recordings were mastered at the Electro-Vox studio in Los Angeles

and were occasionally released with Electro-Vox labels.) Roughly half the songs were in

Hebrew, and half in Judeo-Spanish. During

a New York excursion in summer, 1948, Mayesh made three more recordings

for Me-Re (which bear Balkan matrices), all in Judeo-Spanish. These

latter recordings had more elaborate accompaniment, an "Oriental

Orchestra" led by Theodore Kappas on kanun, with violin and 'oud.

According to his son, these were the best and most popular of his

secular recordings. (26)

For their secular works, both Mayesh and Hazan drew

on well-known Greek and Turkish folk and urban songs, which they then

set to Judeo-Spanish lyrics. For example, Mayesh did his own version of

Missirlu ♪ and transformed a song first known in Turkish as Benim

güzel bülbülüm then in Greek as Kanarini into

Ven

canario. ♪

(25)

The Spanish and Portuguese catalog was bolstered by releases from

London's Bevis Marks choir

and Congregation Shearith Israel in Manhattan. The latter released

a double-78 of

five Hebrew songs from the music of the congregation with Dr. David

de Sola Pool and the synagogue choir. 1951 saw the release of the first

recordings of Sephardic field recording. Six Judeo-Spanish songs

recorded in Paris by a couple from Salonica were included as part of a

larger U.N.E.S.C.O. album.

(Here is Ana Angel singing

Partos Trocados.♪)

Two Makolit Israeli 78s of Sephardic songs as set by the cantor

Nissan Cohen Melamed and performed by

Benjamin Misrakhi

close out the Sephardic 78

era.

Summing Up the 78 Era

At the turn of the past century there was an exuberant expansion of

the repertoire coupled with relatively little experimentation in

performance practice. We need further research to determine if

performances in Salonica, Sarajevo

and elsewhere differed significantly from practices in

Constantinople, the city where most Sephardi commercial master

recordings originated.

Curiously, many prominent Sephardic recording

artists did not record Hebrew or Ladino repertory. Most notable

by her absence was Rosa Eskenazi,

(27) but Abraham Caracach

Effendi, Misirli Udi Avram (a.k.a. Samli Avram Effendi),

Pepron Hanim and Bey Neuman, among others, did not

record Sephardic songs either.

In 1957 Professor Curt Sachs famously defined

Jewish music as music "by Jews, for Jews, as Jews." (28) Sephardic 78 r.p.m.

recordings were surely "by Sephardim, for Sephardim, as Sephardim."

By Sephardim:

Nearly all the vocalists were Sephardim, and I believe that non-Jewish

vocalists were at least conversant with Judeo-Spanish.

For

Sephardim: These

recordings were bought overwhelmingly by Sephardim. (11) The repertoire

exemplifies the then-current interests of the community, enriched by

performers who actively converted folk and popular songs of their host

countries into Judeo-Spanish.

As Sephardim:

The songs were typically learned orally from other Sephardim (or from

recordings that circulated narrowly in the community) and

delivered in keeping with the performance practices of urban Ottoman

music of the time.

Of course, this definition was completely swept away in the second

half of the 20th century. Sephardic

communities that might have nurtured traditional artists were

ravaged by World War II and

subsequent dislocation and assimilation. Meanwhile, the

folk music

revival, the early music movement's "discovery" of Sephardic music and

the world music boom all led to tremendous changes in repertoire,

performance and commercial practices.

|